Reverend Robert Summers, the Episcopalian Minister of McMinnville (1873-1881) had a varied history in Oregon. Robert went from being a settler, to becoming an Episcopalian minister, while he collected Indian artifacts from various reservations in the region while his wife Lucia engaged in botanical collecting.

In 1853 the young Robert Summers, who was born in Kentucky, took up a land claim in Eola Hills, northern Polk County, west of Salem. Summers was a distant relative of the Applegate family. The Applegates famously settled in Oregon in 1844, at Salt Creek, and was one of the first families in the area, becoming important politicians, surveyors and Indian Agents in the state. Its likely that Summers had heard of the opportunities in Oregon through these family connections and came to Oregon to seek his own fortune. But in 1855 Summers sold his claim and moved back to the United States (GLO maps were researched and no apparent drawing exists of the claim).

In the next decade, Summers gets married to Lucia (Susan Ann Noyes), they toured Europe and settled for a time in Kentucky where Summers is ordained a minister. In about 1871, the couple move to Seattle where Rev. Robert Summers becomes the minister of the Seattle Episcopal Church.

In Seattle, the Summers’ interactions with the public reveal their character. They appear very refined, highly educated, dignified, and Lucia presents herself as a fine musician and linguist, as well as becoming something of a naturalist. Lucia begins collecting plant species, insects, and lizards, and spending quite a bit of time in the woods.

In this time period, many people were amateur collectors, called naturalists. These practitioners collected all manner of “curiosities” or “curios”. They would conduct research and present their collections in journal articles. Many of their collections went to museums. Some of the most common types of collections were birds eggs, and nests, insects, plants, Indian curios (baskets, artifacts, bowls, arrowheads) as well as Indian remains. Native skulls were very valuable and in many of the journals, all of these curios were subject to sale. In Oregon, there was a four volume magazine called the Oregon Naturalist (downloadable on Google Books). The impetus of these curio hunters was to put their name on some new species of animal, insect or bird, and immortalize themselves. Many were inspired by the early travels and collections of Lewis and Clark (1805-1806) who collected numerous animal and plant species as well as information about Native peoples, and made maps, all of which were published by 1810. Scottish botanist David Douglas, who came through Oregon in the 1830s and also collected and named numerous plant species (ie; Douglas Fir). These early explorers were extremely popular, and later amateurs, naturalists, sought to capture a piece of that fame.

Lucia Summers appears to have begin as a curio hunter, and because of her education, and her husband’s interest in Indian artifacts, she traveled extensively and became an important botanist/naturalist. Her specimens were sent to Yale University Herbarium , the New York Botanical Gardens, Gray Herbarium at Harvard University, and after her death the bulk of her collection was bought by Phoebe Hearst and is at the University of California. Unfortunately, none of the species she discovered were ever named after her.

In 1873, Rev. Summers takes a new assignment to the Parish at McMinnville, Oregon, which was perhaps something of a homecoming based on his earlier settlement. Summers is the minister at the St. James Episcopal Church which has since been renamed St. Barnabas Episcopal Church. From 1873 to 1881, Rev. Summers spends time on the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation making friends with the Indians there and begins collecting artifacts. He collects some 600 artifacts at Grand Ronde. His collection activities may have been influenced by his wife (or aided and performed by), as all of the artifacts collected are logged into a collection log, with detailed descriptions of what they are, what they are constructed out of, who owned them, how much he purchased them for. His collections are of artifacts, baskets, tools, pipes, bags, carvings many of which were likely made before the reservation was formed, and brought to the reservation by the first generation of Indians.

During his time in Oregon, Summers, and his wife, travel extensively to many other reservations. He collects artifacts from the Siletz Reservation, from the Klamath Reservation, and from areas of eastern Oregon where they collect from burial mounds. He visits Southern to Central California and collects additional specimens from the Indians there. His wife travels with him in 1876, camping with him on their excursions overland and through mountain ranges, and collects botanical species, parallel with Robert’s material and ethnographic collections.

At Klamath, Robert was so set on getting a necklace, that Lucia literally traded the dress she was wearing to get the artifact. Their collection grows to such an extent that for the Grand Ronde Indians, Summers has the only known mortar and pestle they can grind their medicine on. On April 30, 1876, the Summers are visited by a group of Grand Ronde Indians who seek to grind seeds of a Media (Native hemp) to make a medicine to cure an ailing friend.

The Summers leave McMinnville in 1881 and settle in San Luis Obispo, where Robert is the reverend of another church. Robert dies in 1898, and Lucia six month later that same year.

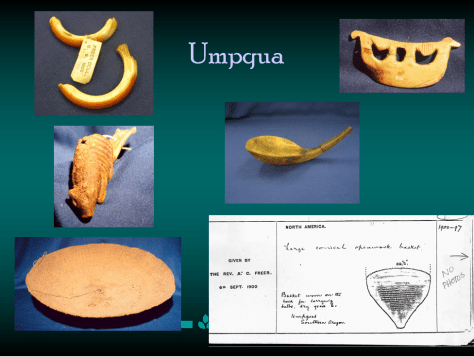

The Summers Collection of Indian Artifacts is over 600 specimens, mainly from the tribes of western Oregon. The bulk is from the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation. The collection passes into the ownership of Reverend Freer who gives the collection to the British Museum in 1900. In 1999, the Grand Ronde Tribe began working to get the collection returned and has had one official research trip to the museum (2000), and numerous consultations in successive years with curators at the museum. Such collections in the British Museum have historically been difficult to repatriate. The Museum has a long history of collecting and buying important artifacts from all over the world. The collections of the British Museum are considered treasures of the nation, and it takes an act of their parliament to return artifacts to the original home country.

The Summers collection represents a rare early collection of artifacts which date from before the reservation was created. Accompanying each artifact is detailed contextual information about it, including the person who sold the artifact to Summers. Ironically, the collection from Grand Ronde was validly purchased with contextual notations that are very progressive for the time period, while much of the Summers’ other Naturalist activities amounted to grave-robbing, now noted by many scholars as among the worst practices in the history of research on Native peoples.

The notion of collecting native cultural traditions, artifacts, stories and languages was an integral part of early anthropology. Many early anthropologists funded their studies by buying and selling artifacts to museums or collectors. Many others sold their ethnological collections to government funded organizations like the Bureau of American Ethnology, later to become the National Anthropological Archives. Some of these amateur collectors were anthropologists in training, and some on salary at the BAE. Salaries were set very low at this time, so that many appear to have traded in native curios to help fund their studies.

This “tradition,” a founding set of principals in the formation of Anthropology today has since been vilified by contemporary anthropologists and the era, and practice named Salvage anthropology/archaeology. Anthropologists and tribes have noted powerfully that salvage anthropology was part of the colonizing traditions of the United States and other European and expansionist nations of the world. At the same time that ethnographers and early anthropologists were collecting and selling native curios to museums, Native peoples were undergoing extreme colonization of their peoples and nations, due to United States and other nations attempts to assimilate their people, take away their lands, and eliminate their claims to their traditional country. In effect, these collectors were taking advantage of the vulnerable status of many Native peoples, in order to collect and sell artifacts, and the collections that now exist in museums are the results of that era.

We see examples of the effects of salvage anthropology today in museum exhibits and archival holdings of Native American and Indigenous artifacts worldwide.

Sources:

Alverson, Edward R. Lucia Summers (1835-1898) First Resident Botanist In the Pacific Northwest, Kalmiopsis, Volume 18, Native Plant Society of Oregon, 2011.

Cawley M. Ed. Indian Journal of Rev. R.W. Summers, Lafayette (OR),: Guadalupe Translations, 1995.

My memory

One thought on “Naturalists In Oregon: Robert and Lucia Summers”