I have always been confused as to why there is a Chemawa Jr. High in Riverside CA. The word Chemawa is from the Kalapuya tribes of the Willamette Valley and designates a village just north of Salem, Oregon. As well there is a Native boarding school, Chemawa Indian School, that began in 1880 located north of Salem that is still operating. In recent research I found there was a pre-existing Chemawa Park in Riverside which predated Sherman Indian Industrial school by one year (1901), and Chemawa Jr. High, built within the former park, which is still operating as Chemawa Middle School. The park was establish by Frank Miller (Riverside a& Arlington Electric Railroad) and also featured a a small zoo- a bear pit for up to 4 animals- and a sports field, field hockey is mentioned (Chemawa Park history). I found that there may have been some influences from Harwood Hall, who was the Superintendent of Chemawa Indian School from 1916-1926 and had influence with the Riverside Chamber of Commerce. He was previously the Superintendent of Sherman Indian School in Riverside (1901-1911), the Perris Indian School before that, and of the local Pala Indian Reservation. He and his wife were upper class socialites in Riverside, where they hosted big parties at their house next to Sherman Indian Industrial School.

Hall was in fact the person who lobbied the Bureau of Indian Affairs to close the Perris Indian School, and move operations to a new location in Riverside. Hall’s reasons for moving the school was because the Perris site was unsuitable for having any agricultural instruction, there was not good soils, nor water, nor room to make this type of instruction successful (San Diego Union and Daily Bee, 17 January 1898). Hall was a professional agriculturalist and consulted on many products in Southern California and so agricultural instruction was important to him. Besides he also saw a greater need for instruction of the thousands of Indian children in Arizona (estimated 8,000), who were poorly provided with education by the BIA, and the new location could host at least 500 students (San Diego Union and Daily Bee, 17 January 1898). It was common to removed Indian children to other states far away from their homelands so that they would find it difficult to escape and return home.

Hall had, previous to the Perris appoint, been the superintendent of the Phoenix Indian School and was reassigned to Perris Indian School in 1897 (Los Angeles Herald, Volume 26, Number 196, 14 April 1897). His efforts lobbying the BIA to move the school were successful resulting in the siting of the Sherman school in Riverside, CA, next to his own property and on property that was owned by his relatives. On July 18, 1901 the cornerstone of Sherman Indian Industrial School was placed and buildings finished July 1902 and instruction beginning in September 1902. Hall oversaw many details of building the facility and served as the first superintendent of the school. Sherman opened with 300 students “collected by Hall,” (Indian student attendance was compulsory) and when completed would have the capacity for at least 700 students (Los Angeles Herald, Volume XXIX, Number 334, 2 September 1902).

The opening of Sherman was not completely smooth, because in September 1902 Hall was forced to move about 60 students from Sherman to the old Perris school for unknown reasons, most likely they had too many enrollments and not enough dormitory space that year. Several new dorms were added in the following years. This necessitated hiring of additional teachers for the Perris school until the problem with the new campus was solved (Los Angeles Herald, Volume XXIX, Number 348, 16 September 1902). Enrollments each year climbed at Sherman to at least 800 by the time Hall left Sherman. Hall took an assignment as Inspector of Indian schools (1911-1916) (Riverside Daily Press, Volume XXXIV, Number 58, 8 March 1919), before he was reassigned to Chemawa Indian school (1916) in Salem, Oregon to get the school in order and expand enrollments.

Hall’s time spent at Chemawa as the Superintendent from 1916-1926. Mentioned in many newspaper articles is his Indian art collection, baskets, pottery, and other woven works, and both he and his wife were collectors and perhaps knowledgeable about the art forms. Mrs. Hall gave a presentation on Indian pottery and basketry at one Philanthropic Educational Organization sisterhood socialite gathering at their home (CJ Oct 20, 1921). Particularly noted in the Oregonian newspaper article (Nov. 2 1919) was a selection of baskets from Oregon, but the Halls are better known for their collection of baskets from the Mission Indians of Southern California. This caught my attention because Indian school policy discourages teaching students traditional Indian arts and made the students learn approved European/American arts. There did seem to be a weaving program at Sherman and perhaps Chemawa, but they had to use approved materials, not native materials and it appears they also had to use approved weaving styles, wickerwork is mentioned. (Anything further about the art and craft programs, advice as to where to go to find more would be great. I have a request in to the Museum at Riverside after I discovered that the Hall collections and archives are.)

“The collection of Baskets represent the wanderings of 35 years of Mr. Hall’s life, during which time, as an Indian inspector, he visited practically every reservation in the United States and Alaska. At various periods he was in Oklahoma, Dakota, Arizona, California, Nevada and Oregon. Some of the pieces of handicraft are absolutely beyond money value, in his own opinion. Many of the single baskets, if offered for sale, would bring hundreds of dollars. Every one, he explains, was intended for a specific use, each basket-making tribe producing an entirely different type from its neighbor. They are intended for cooking, storing and like purposes, much as our own modern dishes, pans, buckets and baskets. Two varieties common to every chief’s following were the wedding and ceremonial baskets. Great care is taken in the making of these grass vessels and according to the size and pattern they require long periods of time to fabricate. An old [native woman] always produces the best handiwork, because patience and experience are two of the requisites of a successful basketmaker. She may spend several years completing a piece.”(Oregonian Nov. 2, 1919)

It also appears the Halls and perhaps other socialites used Indian arts collections and Indian students performing dancing and singing to gain status in the local society. Newspaper articles from the era for Riverside and Salem, suggest that Harwood and his wife moved into Socialite circles and invited socialites back to the schools and their well decorated supervisor’s houses at both locations for entertainments. They would host socialite parties, luncheons with tea and cakes, poetry readings, dramatic plays (Story of Yucatan- OS May 22, 1922), card games ( OS April 17, 1921) and other displays of the civilization of the Indian students. The parties and occasions were nearly constant throughout the year with many different women’s and men’s organizations, clubs and committees invited to the school and to the Hall’s house. At least one Oregon Governor, Ben Olcott, was regularly present at dinner parties, all food was prepared by the students, to again display their “civilized” training in the culinary arts, complete with dinner entertainments of the aforementioned plays, readings, displays of Indian language recitations etc. The socialite organizations mentioned include; Multnomah Daughters of the American revolution, Philanthropic Educational Organization sisterhood, Kiwanis, Interchurch association, and others.

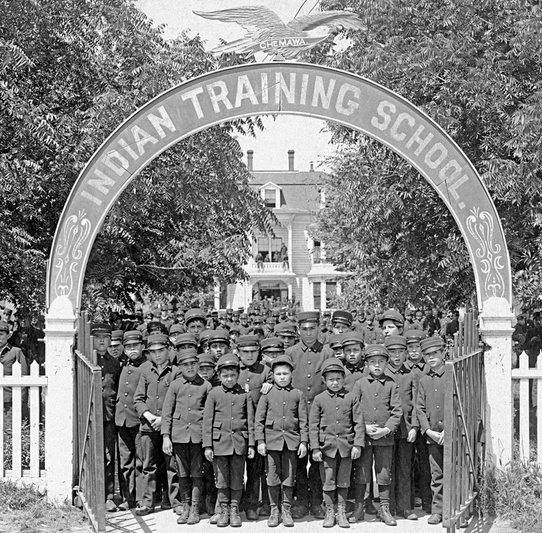

The Halls and their guests appeared to delight in the juxtaposition of “Indian” students, formerly labelled uncivilized and birthed by uncivilized parents on reservations, reciting Shakespeare, Greek, Roman, and popular plays, singing religious and popular songs, and playing music on brass instruments, and orchestral violins and cellos. The students also put on exhibitions, open houses, dances (OS May 3,1921), industrial arts exhibits (OS June 1, 1921, June 2, 1921), and numerous dinners for local socialites and out-of-town dignitaries, including in one instance Governor Pat Neff of Texas (Roseburg Sun June 4, 1924). Graduations were programmed to be exhibitions and entertainments for area citizens (CJ May 30, 1922) to come see parades and Indian children dressed in military outfits marching about the grounds organized in battalions to show off their training at the schools (OS June 10, 1921).

As noted, the Halls are reported in articles in Oregon and California newspapers as having had a large and impressive Indian Basket collection. This collection they used to decorate their parlors, at both Sherman and Chemawa, where they would host many of their socialite meetings. This fact is hugely ironic because the Halls clearly valued traditional Indian arts, and used their collection to impress their high society visitors; yet in the Indian service schools – which Harwood Hall administered – they discouraging Indians from practicing traditional Indian arts, and were having a huge effect on the next generation of Native artisans through assimilative education.

The Hall’s collecting activities were part of the salvage anthropology and naturalist collecting traditions of their time. This was a period from the mid-19th century to well into the 20th century, when anthropologists and others thought the tribal people were disappearing as a people, and with them would disappear their amazing art creations and cultures, a notion which prompted madscramble collecting for decades on all manner of traditional Native American arts. Many of these collections became famous and museums today hugely benefit from having been gifted collections of Native arts. At the same time many of these very same collectors were trying to gain some measure of fame and wealth from the artwork of Native people, without choosing to help save Native people the practitioners and creators of tribal culture, while the Halls were actively working in the Indian schools, an industry which sought to destroy Native culture.

There are few statements that cause more cognitive dissonance than the following from an interview with Harwood Hall,

“As time passes there will undoubtedly be a great increase in the value of a genuine Indian basket, for the art is rapidly dying our among the red tribes, an art that is as old as the earliest aborigines that roamed the forests of the old world. Even now it is only the older generation that turns to this pastime, for the younger woman feels that the white man’s utensils may be had so cheaply that it does not pay to put in weeks or months weaving a bread bowl. Besides she is progressive, and has probably availed herself of the opportunities offered by the white man’s education and taken up activities of a more remunerative nature.” (Oregonian Nov. 2, 1919)

Recall, that Indian education was compulsory, Indian children would literally be forcefully collected from reservations, by Indian agents and Indian school supervisors, and taken by wagon to the industrial schools and forced to remain. There was no choice by the parents whether their children would go to the BIA schools.

When Hall left Chemawa Indian school and retired, he and his wife went back to living in Los Angeles. Harwood died in 1928 after several years of illness, but he and his wife had taken positions with the BIA helping graduated students find jobs in the LA area.

The plays, poetry readings, exhibits, dances, and songs by students were displays of the beneficial effects of assimilation education and progress of the Indian children towards civilized skills, were used as part of a strategy by the Halls to effectively lobby the Indian Office and Congressmen, and local non-governmental organizations, for support and more funding for the schools Harwood Hall administered. The Sherman and Chemawa schools would regularly get visitors from the Indian bureau and they would likely leave impressed with the progress made by the students. Likewise, the same effects of these entertainments would impress the local socialite groups whom Harwood and his wife would literally wine, dine, and entertain their gentile visitors and then lobby for donations or their support for additional resources for the school. The Halls were highly effective at this, worked as a team in both women’s and men’s society circles and were able to gain donations and investments from the state of Oregon as well. In 1921 Senator Charles McNary secured $257,000 for Chemawa Indian School to built a new boy’s dormitory and a better heating system. The appropriation was championed by Harwood Hall, who noted the promises of McNary and Congressman Hawley for an appropriation, and it is quoted as being announced by McNary, Hall, and by the Salem Commercial Club (Oregon Statesman Feb. 11, 1921, p.1). The new building project would have the federal money coming back into the community through a local construction company and in workers’ pay. The Indian school then was targeted for local economic development based on the purported needs of the poor Indians for civilization. February 23rd, 1922 the boys dormitory was funded at $60,000 in the Senate Appropriations Committee (Oregon Daily Journal 2/23/1922).

McNary worked for decades on behalf of Chemawa and in 1933 managing to save the school from a plan by Commissioner Collier for closure with a reduced student attendance of 200, from its previous 1000. The new Chemawa curriculum was based on a vocational education model. In 1922 McNary also championed a new policy to allow Chemawa students to complete their high school while living in Salem, because completing school at Chemawa did not give a high school diploma. This plan hinged on the charity-minded white citizens in Salem taking a student into their homes to live while they took up to two years to complete high school at Salem High (now North Salem High). In the meantime the students would work in the households to pay their way. This managed to change the BIA policy to allow students to remain at the school to 21 if they did not cost the BIA for their education or board (ODJ Oct. 6, 1922). (This Program needs further investigation because it could have been easily exploited by white residents getting free in-house cleaning and other labor from Indian students while in the program. Did the students have freedom to leave, and how were they treated?) Mentioned in the newspapers was the plight of Alaskan Natives who had no or few schools in their remote communities. Chemawa become the targeted high school for many students from Alaska for decades.

Many of the Indian artwork collections are now in local and national museums. The Harwood Hall collection is at the Museum at Riverside. I have yet to see what baskets are in the collection and I will be interested to discover which cultures in Oregon had baskets collected by the Halls. One question is whether the Halls got the baskets from the reservations, or did they get the baskets from students attending the school, or perhaps their parents.

All of this is quite interesting and displays a theme for Indian schools which has not well been covered in scholarship. The role of the Sherman Institute promoting tourism at Riverside, is previously covered by Nathan Gonzales (Gonzales, Nathan. “Riverside, Tourism, and the Indian: Frank A. Miller and the Creation of Sherman Institute.” Southern California Quarterly 84.3/4 (2002): 193-222.). William Medina has addressed how Sherman institute used Indian children as a marketing ploy to raise money for the school (Medina, William Oscar. Selling Indians at Sherman Institute, 1902–1922. University of California, Riverside, 2007.). But the socialite influence dimension, the strategy by the Halls to attract support and money for the schools he supervised through socialites is something new.

See the free and searchable Oregon Historic Newspaper site at UO for the Oregon Newspaper archives, and the California Digital Newspaper site for the California Newspaper archives.